Impaired Driving and Over-80: Are historical maintenance records for a breathlyzer device are first or third party records in impaired driving investigations?

Published On: Nov 03,2018

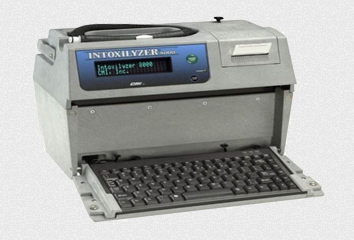

In an important disclosure decision from the Supreme Court of Canada (the “SCC”) provides guidance on legal standard imposed on Crown Prosecutors and policing services to disclosed historical maintenance records that pertain to the breathalyzer device used in the context of impaired driving investigations under section 253(1) of the Criminal Code of Canada (the “Code”) or their predicate sections. Critical to the SCC’s determination was the “likely relevancy” of the records sought by the defence. Despite a well-argued case by reputable and senior defence counsel from Calgary, Alberta, the SCC ruled, in Regina v. Gubbins, 2018, SCC 44 (and the companion cases), in an eight (8) to one (1) majority, as follows, in relevant part:

First, the historical maintenance records sought by Mr. Gubbins, through counsel, that related to the breathalyzer device used in the investigation of a charge of driving “over 80” was not “first-party disclosure”. Under the cases of Regina v. Stinchcombe, 1991 CanLII 45 (SCC), [1991] 3 S.C.R. 326 at pp. 336-40; Regina v. Quesnelle, 2014 SCC 46 (CanLII), [2014] 2 S.C.R. 390, at para. 11.and their pedigree, the Crown has a broad duty to disclose all relevant, non-privileged information in its possession or control to persons charged with criminal offences. Disclosure of this information allows the person charged to understand the case she or he has to meet and permits him or her to make full answer and defence to the charges. However, in this case, the SCC found that they were third party records, and the defence must demonstrate their “likely relevance” at an application for production. However, “time-of-test” records, which show how the device was operating when the accused’s sample was taken, are “obviously relevant” and therefore are first party disclosure.

On this concept, the “likely relevance” standard is significant, but not onerous. It allows courts to prevent speculative, fanciful, disruptive, unmeritorious, obstructive, and time consuming requests for production. What is more, the he duty of the police to disclose first-party material is limited to the “fruits of the investigation” and information “obviously relevant to the accused’s case” (at para. 21). Neither includes “operational records or background information.” In citing Reginav. Jackson from the Ontario Court of appeal, the Court posited:

[22] The “fruits of the investigation” refers to the police’s investigative files, as opposed to operational records or background information. This information is generated or acquired during or as a result of the specific investigation into the charges against the accused. Such information is necessarily captured by first party/Stinchcombe disclosure, as it likely includes relevant, non-privileged information related to the matters the Crown intends to adduce in evidence against an accused, as well as any information in respect of which there is a reasonable possibility that it may assist an accused in the exercise of the right to make full answer and defence. The information may relate to the unfolding of the narrative of material events, to the credibility of witnesses or the reliability of evidence that may form part of the case to meet.

In its normal, natural everyday sense, the phrase “fruits of the investigation” posits a relationship between the subject matter sought and the investigation that leads to the charges against an accused.

This case is important and contributes to the existing case-law because the SCC’s previous decision in Reginav. St‑Onge Lamoureux, [2012] 3 SCR 187, 2012 SCC 57 (CanLII), did not decide that maintenance records are “obviously relevant,”and expert evidence establishes that the issue of whether a device was properly maintained is immaterial to its functioning at the time the sample was taken.

What is more, the Court held that the constitutionality of the statutory presumption of accuracyof breathalyzer devices is not jeopardized by the holding that historical maintenance records are third party records. The defence can use time-of-test records and testimony from the technician or officer involved to challenge the presumption. A defence is not illusory simply because it will rarely succeed. At paragraph 47, the Court stated: The statutory presumption of accuracy refers to the specific results generated by the instrument at that time. The only question that must be answered is whether the machines were operating properly at the time of the test ― not before or after. The time-of-test records directly deal with this. The maintenance records, according to the expert evidence, do not.

Conversely, Justice Côté . dissented. In his decision, he held, that would have held that maintenance records are “obviously relevant” to rebutting the statutory presumption of accuracy, and are therefore first party disclosure. Justice Côté also would have held that the constitutionality of the statutory presumption of accuracy depends on the ability of the defence to access maintenance records. The rationale of this decision was summarized in the following terms:

Holding that only time‑of‑test records produced by the instrument can demonstrate malfunctioning effectively assumes that the machine is infallible. This confines the defence to arguments raising a doubt as to the instrument’s operation, contrary to Parliament’s intent to make malfunctioning and improper operation two distinct grounds for rebutting the presumption of accuracy. Recourse to third party disclosure will, in practice, be illusory. For an accused to have a real opportunity to show that an instrument was malfunctioning, an expert must have an evidentiary basis either to opine as to the possibility that the instrument malfunctioned or to establish the likely relevance of other information to be sought through third party disclosure. Providing nothing by way of first party disclosure forces accused persons and their experts to resort to conjecture and speculation.

And he concluded at paragraph 86:

[86] Finally, it is my view that disclosing maintenance records as first party records is not only consistent with St-Onge Lamoureux but also serves the interests of justice. Where maintenance records reveal no issues, their disclosure may compel the accused to plead guilty. Where they reveal certain issues and an expert is of the opinion that these issues may prove that the instrument malfunctioned, the maintenance records provide a basis for the accused to raise such a defence or to make subsequent O’Connor requests in a grounded, non-speculative manner.

While this decision may seem innocuous at first glance and of limited application to only breathalyzer devices, it is likely that the SCC has paved the path in anticipation for other technological devices used (or to be used) by policing services throughout Canada. The logic of the Court’s decision will have an impact on future disclosure motions that pertain to software and hard-ware used by police and their applicability to the constitutional rights of accused persons.

If you have been charged with impaired driving, “Over-80”, refusing to provide a sample, contact Mr. J. S. Patel, Barrister for a free thirty minute initial consultation over the phone. Contact 403-585-1960 to arrange an appointment.